|

|

|

Gelatin Dry Plate Photography |

|

by |

|

A little over a year ago, I purchased the photographic estate of Alfred Schellenberger. ‘Schelly’ – as he signed his prints – was a young army photographer during World War I. In France, he photographed everything from the dead in the trenches to French peasants in the fields and classic landscapes. He used 4x5 glass plates, 4x5 film negatives, and Whole Plate negatives (6.5 x 8.5 inches). He apparently did some of his own contact printing, but in addition, he seems to have had many of his negatives commercially printed. While his life and the content of his photography were extraordinary, his photography workflow was probably typical for a professional of the day.

Mr. Schellenberger’s life and photography exemplify the breadth of photographic history research. The most obvious branch of research involves the content of the images. Someone was then/there with a camera – our glimpse into the past. This is the level of most museums and collections, and the purpose of most archives.

If a photographer leaves a legacy of work, or has an interesting life’s story, he or she becomes as much a part of history as the images, and we are primarily studying a biography. An additional layer of exploration involves the process that was used by a photographer. Here is where history meets art history. Unfortunately, even in good collections with caring and professional curators, this part of the story of every image often goes untold. If I go down to my local museum (a wonderful little place staffed by proud volunteers who are there to preserve, celebrate, and pass on the history of our small logging and fishing community) I can ask to see the photographic collection. Because the curators want to preserve the original prints and negatives, they have painstakingly copied the originals and what I will see are RC paper or digital reproductions. I will be able to see images, but the images will be removed from the process and materials by which they were created. The great majority of historical photographs are in small, local museums like the one in my town. Most of the public recognizes a daguerreotype, and maybe even a tintype. A knowledgeable curator will know whether a print is albumen or platinum, but the technical nuances of the vast bulk of silver gelatin emulsion-based photography are a cipher to both the public and the professionals. It’s not our fault.

History in a Lockbox As excellent a publication as it is, The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, 3rd Edition, 1993, doesn’t have an entry titled ‘Dry Plate’. There is ‘Wet Collodion Process’, ‘Autochrome Process’, ‘Daguerreotype’, ‘Albumen Process’, and a host of others – many decidedly obscure. Dry plates are relegated to a subheading under ‘Photosensitive Materials History’, which outlines in two brief paragraphs discovery in 1871 to worldwide commercialization less than ten years later. Buried, unsaid, within those two paragraphs is a story without rival of industrial secrecy, cutthroat competition, proprietary patents, and consumer brainwashing. George Eastman was a clever inventor, but just as important to our tale, he was an inspired businessman. He set out to form a monopoly on photography and very nearly succeeded. Beyond his undeniably innovative discoveries in photographic science and engineering, his greatest achievement was in changing the psychology of photography. That Kodak’s slogan, ‘You push the button; we do the rest’, made photography accessible to everyone is well known. What is only recently becoming understood is the cost of commercial convenience to photographic history. For a hundred years, silver-based materials were ‘photography’. The commercially produced products were so varied and so excellent it was easy to convince photographers to purchase their materials rather than make their own. In the English edition of La Technique Photographique, 2nd edition (Photography Theory and Practice), 1937, by L.P. Clerc, the author states, without qualification, "the manufacture of gelatino-bromide plates, films, and papers is exclusively an industrial process" (p 130). Many professionals and serious amateurs continued to develop negatives and print their own photographs, but no one questioned that silver gelatin materials were necessarily ‘factory made’. There wasn’t a need to question. The variety and quality of plates, film, and paper that Kodak and others were selling in 1945 is amazing, and today, to those of us who lust after materials lost – haunting. At some point, for some reason (because digital could not yet be blamed) products began disappearing at an unprecedented rate. And, when a product disappeared off the shelves, there was no getting it back; there was no home darkroom or cottage industry alternative. The details of manufacture were locked away, or worse, died with key development people. Although many materials were replaced with an ‘improved product’, often these had far less potential for creative control than those lost.

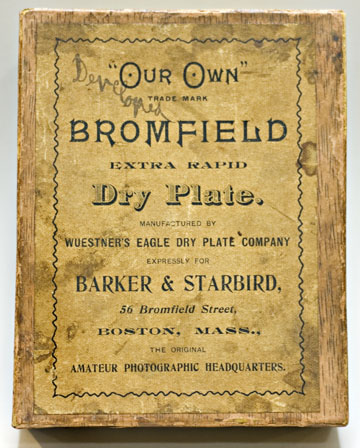

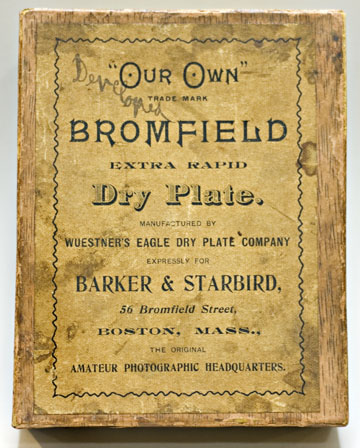

Reclaiming Our Photographic Heritage I believe it is important to understand that our ignorance of silver gelatin emulsion making is a deliberate product of marketing and market control. After a hundred years of propaganda, we don’t even know that we can know how to make d.i.y. emulsions. There is no question that variable contrast paper and the more modern roll films may be beyond the home darkroom, at least for now. Fortunately for us, those products are still available and probably will be for some time to come. We are in an enviable (and I think exciting) position. We may not know all the details of how to make all possible silver gelatin emulsions, but what was once done with the very simplest of tools and materials can be done again. Dry plate negatives are the perfect starting place. ‘Dry Plate’ ‘Dry Plate’ is generally agreed today to mean gelatin dry plates: a gelatin-based suspension of photosensitive silver coated on glass and dried before being taken out into the field. When we refer to ‘wet plate’ we mean the wet plate collodion process, where plates have to be prepared and processed in the field, one at a time for each exposure. Historical research can get confusing, though, because of some overlap in terminology. Although wet plate collodion photography was the standard for more than twenty years starting in 1851, and was the medium for the iconic photographs of the American Civil War and the Crimean War, the process was inconvenient (to say the least). The photographer was required to travel with a complete darkroom that had to be assembled for every exposure. The photographic Holy Grail of that day was a sensitized plate that could be made up ahead of time in a darkroom, and keep long enough to get out on location for exposure and back again to the darkroom for processing. Any number of methods were tried, including coating the collodion with albumen or varnish. The methods were all called ‘dry plate’ at the time, but any increased convenience couldn’t outweigh the resulting reduced sensitivity, and they never gained popular support. In 1871, ‘dry plate’ as we know it today was invented when Richard Leach Maddox, a doctor who was also a photography enthusiast, discovered that gelatin made a dry plate with greatly increased sensitivity – the perfect twofer. Word got around at viral speed, considering the Internet and twittering hadn’t been invented. It wasn’t long before photographers, both professional and amateur, were experimenting and inventing and sharing their results. Bennett, Abney, and Eder are names from those times. The writings of these men are among my favorite photographic literature. It’s not just that I can wrap my mind around the chemistry and techniques they used, it's the enthusiasm and optimism. They were excited! The discoveries and improvements in recipes and techniques came along almost daily. In 1878, Robert Bennett exhibited pictures that captured movement and he freely published his emulsion making method. Twenty-seven years of wet collodion photography became history overnight and the race was on to corner an obviously lucrative market. With wet plate collodion, except for the raw chemicals and bare glass, there wasn’t much potential for commercialization. Dry plate was different. Albumen printing paper had been made commercially for years. Manufacturing negatives allowed the commercial circle to close. By 1880, every industrial country in the world was manufacturing photographic materials. What rapidly followed can be understood best by thinking back to the heyday of Microsoft, when every little IT startup dreamed of being bought up by Bill, and those that threatened the Empire were subject to involuntary takeover. This model had been perfected by George Eastman. The sharing of research dried up almost overnight. Photography publications carried articles on how to use the newly available materials and were remarkably similar to the photo magazines of today. It’s hard to tell how many photographers continued to make their own emulsions. Most quite reasonably chose to buy products that in many ways were better than they could produce themselves. Cottage-scale companies suffered and went out of business as a few photographic conglomerates came to dominate both the market and innovation. Every new discovery became a trade secret religiously kept in-house. In 1929, E. J. Wall wrote in his book, Photographic Emulsions, "This trade or professional etiquette, which prevents the manufacturer from giving information as to his emulsions, is a serious stumbling block in the advance of our knowledge of the real whys and wherefors of emulsion making. In the early days, and it must not be overlooked that the gelatino-bromide emulsion was discovered by an amateur, the technical journals were filled with accounts of experiments in emulsion making; but since the commercial manufacture of plates an impenetrable wall of silence has shut down, that one might as well try to pierce as get through a modern safe with a knitting needle. This is, of course, explicable and understandable to some extent in view of commercial rivalry, but there can be no doubt that much valuable information might be given without violating professional secrecy." In 1942, C.E. Kenneth Mees, the founder and first director of the Kodak Research Laboratories, and a prolific photographic science and history writer, wrote in the preface to the first edition of The Theory of the Photographic Process, "One omission in the book requires explantion (sic). A book on the theory of photography should contain a chapter on emulsion making, discussing various methods of procedure and their effect upon the finished product. The author’s knowledge of this subject has been acquired in confidence, however, and he is not entitled to publish the material with the frankness which alone would justify any publication." So, where does this leave us if we want to learn all we can learn about silver gelatin emulsions? I believe that if we start from the beginning of the technology and move forward in the same way as the original researchers and photographers, we can, in essence, reinvent photography.

A Brief History of Emulsions on Glass

D.I.Y. Dry Plate 101 Emulsion Basics: A dry plate emulsion in its simplest form need be nothing more than gelatin, silver nitrate, potassium bromide, water, and ammonia combined in the right order and heated for a period of time, then coated on glass plates and dried. This is the method described by Dr. Eder in 1881. All emulsions build on this simple model. The bromide may be added as ammonium bromide and frequently, potassium iodide is added. The many variations possible are as much a matter of the cooking method used as of the ingredients added. Two important controls are how fast the silver solution is added to the gelatin and bromide and how long and at what temperature the gelatin is heated at the end of the process. The first (emulsification) affects the size of the grain, and the second (digestion) influences the sensitivity of the emulsion (i.e. the speed). Silver gelatin emulsions can be ‘unwashed’ or ‘washed’, depending on the surface that is intended for coating. Salts that are a by-product of the emulsion process will be absorbed by paper, but will crystallize out when coated on an impermeable glass or film surface. The resulting crystal formation will ruin the surface of a plate, so it is necessary to remove (wash) the salts before the final steps preceding coating. An emulsion is ‘washed’ by first allowing it to set up under refrigeration. The cold, hard lump of silver-salted gelatin (now light sensitive) is shredded and these shreds (sometimes called ‘noodles’ or ‘worms’) are rinsed several times in very cold water. The salt-free (and lower pH) shreds are melted and then heated with additional gelatin or other ingredients specific to the recipe and ‘digested’, the step where the emulsion gains its last bit of speed. The Lightfarm website currently has three washed negative emulsions. http://www.thelightfarm.com/Map/DryPlate/Recipes/DryPlateSection.htm. The simplest was developed by Kevin Klein and follows the Eder model. The other two are a bit more complex and are hybrid modifications from a number of literature sources. Any of the three recipes is a good starting place, but there is such a wealth of recipes to try in the old literature, it’s hard to settle on one!

Gelatin: Here is where it’s necessary to address the only real wrinkle in our ‘industrial anthropology’ quest: Gelatin – the almost magical ingredient that defines silver gelatin emulsions. Gelatin was used for decades after its discovery as an emulsion base before scientists discovered what made it tick. Most obvious and easy to understand is its action as a protective colloid – the gelatin keeps the silver grains suspended and helps them grow to controlled sizes. Gelatin melts and sets again and again with little change in character. It dries hard. But gelatin did something else. It greatly increased the sensitivity of the emulsion. Modern photographic gelatin is a highly purified and standardized product. The early gelatins used for photography were anything but. There were dozens of brands in use, each with its own characteristics. Jelly strength (hardness) was easy to measure, but it was harder to quantify the sensitizing ability of a particular brand of gelatin or even between different lots of the same brand. Stories grew of secret herds of cattle grazing on secret fields of secret plants that produced the ‘fastest’ gelatin. When it was noticed that gelatin made from cows that had grazed on mustard fields was especially effective, it wasn’t long before it was discovered that sulfur compounds in gelatin increase the speed of an emulsion. This was a great discovery for photographic science, but today it causes photo-technique detectives no end to grief. It’s hard to know the characteristics of ‘Nelson’s No 1’ gelatin or ‘Heinrich’s’. For us, it’s as much trial and error as it was our photographic predecessors. A good starting point for any new, unknown recipe is to add a few drops of plain hypo (sodium thiosulphate) or Steigmann’s gold sensitizer. (http://www.thelightfarm.com/Map/DryPlate/Recipes/DryPlateSection.htm) Beyond the technique of adding quantified additions of chemical sensitizers to modern, ‘inert’ photo grade gelatin, I am particularly interested in investigating the different food grade gelatins currently available. Gelatin is one of the two indispensable components of silver gelatin emulsions. I’m uncomfortable counting on 250 bloom photographic gelatin remaining forever available to home darkroom chemists. More important even than having a materials ‘safety net’, is learning how to follow the old paths. A hundred years ago, every emulsion company had a testing protocol for each batch of gelatin that hit the loading dock. For both the purpose of emulsion making for personal art’s sake and for the history of it all, understanding gelatin is as important today as it was in 1871.

Glass: Here’s where we get lucky. Basic glass manufacture is unchanged from the 1880’s. Dry plates were made with both 1/16 and 3/32 inch glass (approx. 2 mm - 2.5 mm) and these thicknesses are still available. There may yet be specifics of UV filtering characteristics to tease out, but it’s my feeling right now that this is a minor issue. For our purposes, cheap, simple glass is the best glass. Chemicals and Lab Equipment: A surprising amount of the tools needed for emulsion making can be found at the household goods section of a larger grocery store. If you already have a modest darkroom, you probably have most of what you’ll need to get started. Much of the basic chemistry is available from the larger alternative photography supply companies. Some of the more exotic ingredients can be found at a chemical supply company. Although most chem houses require a business license, I’ve had no problem with my photography business license and a letter explaining my intent. Coating: Making a basic emulsion is a surprisingly straightforward affair. Coating glass plates with the emulsion can be a different matter. The first gelatin dry plates, even those made commercially, were hand-poured from a tea pot. Handcoating was a skill left over from wet plate collodion. George Eastman realized from the start that a machine was needed for true commercial output and put one on-line in 1880. Today, we have basically two coating methods available to us (at least until some smart inventor/entrepreneur comes out with a 21st century small scale coating machine.) Hand-pouring works just fine – with a bit of practice. The result is a decidedly ‘handcrafted’ look, but that can be just what distinguishes an artist’s work from a commercial product. Because I can’t seem to get the hang of a good hand pour, I coat with a glass emulsion well (sold by me through The Light Farm) and a glass coating rod (Corning brand ‘Puddle Pusher’.) For more information, please go here: http://www.thelightfarm.com/Map/DryPlate/PlatePrep/DryPlateSection.htm Printing Glass Negatives: This last step is where it’s great to live in the 21st century. We have more printing options available to us than Dr. Eder and his contemporaries did in 1881. This means that we have (much) more leeway on the way to perfecting our skills. Thin plates can be scanned in a flatbed scanner or photographed on a light table with a digital camera. Dense plates can be enlarged onto a variable contrast paper, fiber or RC. Larger plates can be contact printed, with burning and dodging, on handcrafted paper, or the new Lodima silver chloride paper from Michael A. Smith and Paula Chamlee. Caring for Dry Plate Negatives I can’t give better advice than that of The Society of Rocky Mountain Archivists. Go to their website and type ‘dry plate’ into the search box. http://www.srmarchivists.org/

Suggested Literature |

|

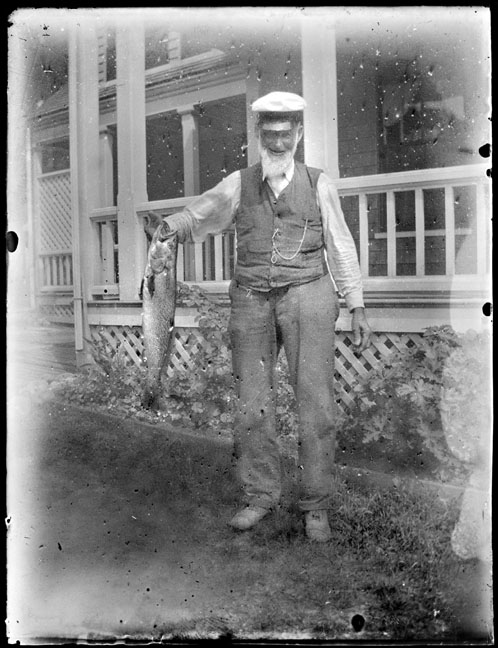

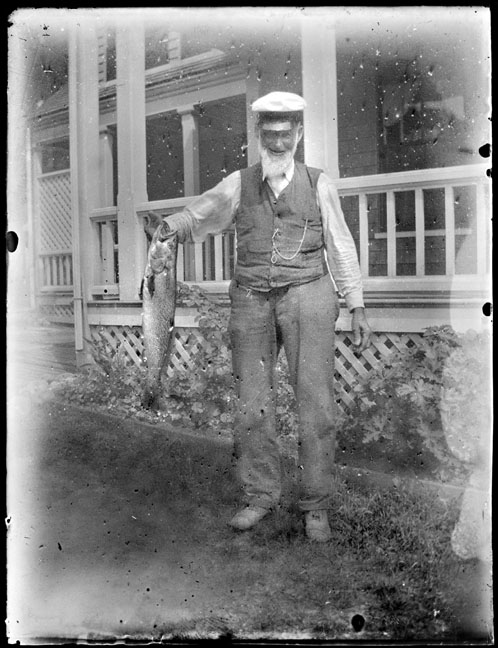

Modern Dry Plate Photography Images by Denise Ross

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Biography I have spent my life (hopefully only half my allotted time) wedged between science and art. Fifteen years ago, after many years of alternating photography classes and science classes, I flipped a coin and took a Master's degree in botany. I owned a seed lab for a number of years, but in the end, photography won the day. For the last three years I have worked full-time investigating the art and science of handcrafted silver gelatin emulsions. I can’t imagine anything in photography more satisfying or more important. In addition to The Light Farm, my photography can be seen at http://www.dwrphotos.com. |

Copyright © The Light Farm |