|

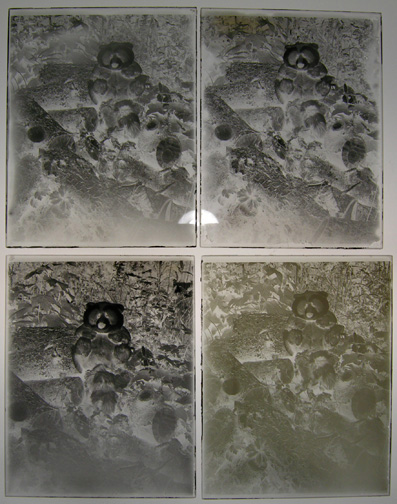

Be it art, science, or magic, there is a wonderful amount control of

density and contrast possible with the old emulsions. I'm

currently working with a simple matrix combination of two emulsion

recipes and four developers. It is my goal to make a well-exposed

plate, no matter the lighting circumstances, and then print that plate

on a custom complimentary paper/developer combo, resulting in a final

print that reflects my original visualization. Dream Big!

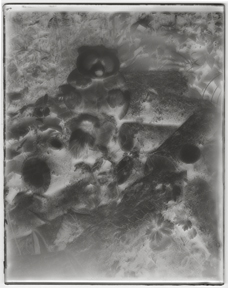

The concept of curve control has been known by every photographer who

has ever shot b&w sheet film: 'Expose for the shadows and develop for

the highlights'. By adjusting the length of exposure and the time

of development, you can control the appearance and printability of your

plates. The following four Panchos illustrate this idea.

|