Digging into X2Ag-Ortho, p.2

March 26, 2012I've let too much information stack up. It's time to get some of it organized on virtual paper. This is as much a research journal as a blog. It is where I keep most of my notes and observations. I go back constantly and look at the older entries for comparison with my current work. So, for my sake, as well as for anyone else reading this, I'll try to make sense of it all. To that end, I'll be posting a short page a day for the next several days.

Even if it weren't the only way to learn this stuff, there would be an excellent reason to become an industrial archeologist in order to study emulsions. I'm learning more than just recipes, and more even than the chemistry involved. I've gotten a glimpse through a time portal. I think I can imagine a lot of what went on in the emulsion laboratories eighty to a hundred years ago.

(Scene: A shout rings out from across the hall.) "Hey, Joe! I think I've got something different here. Send in the test boys to work up a data sheet, and we'll slap a new yellow box around it! We'll call it X-something or another!"

They didn't really understand the deep chemistry and physics of what they were doing. It was only about 40 years ago that all the research started coming together. The old guys were highly trained scientific engineers, and meticulous in their habits, but they were working with silver gelatin emulsions—highly chaotic systems. The tiniest permutation in one step can send ripples through the whole system. Fortunately, precise duplication of conditions will result in precise duplication of results. If you stumble on a 'good' recipe, and if you have good work habits and notes, you can make the exact same recipe over and over again. At least, that is, since the mysteries of gelatin were figured out.

It wasn't until 1925, after almost 50 years of silver gelatin emulsions, that S.E. Sheppard deciphered the mystery of sulfur in gelatin and its relationship with sensitivity. Until then, emulsion workers resembled the Magician's Apprentice. Each batch of new gelatin had to be tested for a range of characteristics before use. The most amazing mythologies existed—right down to the breed of cow. But, for all that, they still managed to make gorgeous films and papers. In a lovely bit of collateral serendipity, beautiful things could happen because of the excellent work habits and notes the emulsion makers were forced to keep in order to replicate their results despite ignorance of quantum mechanics and computer modeling.

Today, we're in an upside-down world from theirs. We know what can be done, because it has been done. On the other hand, most of us are unequipped by education or interest to dig into the deep chemistry and physics required to really understand our emulsions on a quantum level. Most of the exact recipes of the early emulsions are lost forever. They, and many ingredients specific to a particular recipe, went to the grave with that guy who shouted out to Joe.

None of that matters. If we know a few facts and techniques, and one or two basic foundational recipes, we can make our own excellent emulsions—tailored to our own artistic vision. In that, we are in precisely the same place as the early emulsion makers—the same men and women who made the materials that have stood the test of time and beauty.

Comparing a Few Films

Besides "speed," and to a lesser extent, spectral sensitivity, grain is the most commonly perceived differentiator of the various films.

It is pretty much a non-issue with handmade emulsions—with any emulsion really, except for high magnification enlarging.

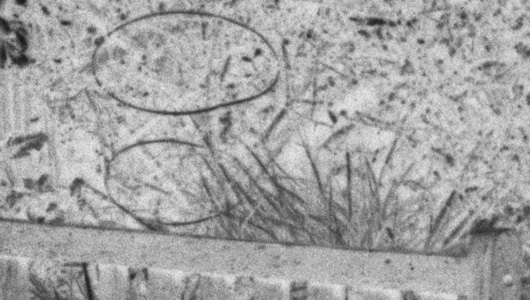

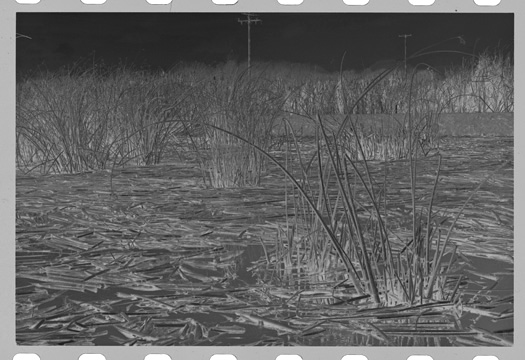

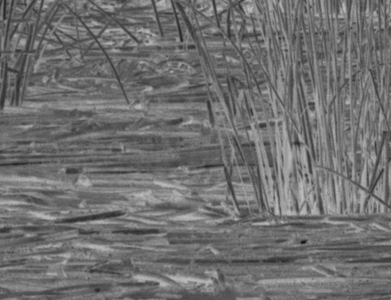

Below: A comparison of grain with identical scanning and as close as possible identical crop magnification.

X2Ag-Ortho (Exposed without a yellow filter.)

Kodak TRI-X 400

Kodak PLUS-X (ASA 125)

Two categories of film stand apart—the modern, flat/tabular "T-grain" emulsions and the older, extremely fine grain, slow emulsions.

Kodak TMAX 100

Ilford PanF (ASA 50).

Continued...