17. Ammonium Bromide Plain Silver Negative Emulsion, part 1 |

OK. Time to start mixing things up a bit. There is a world of emulsion possibilities to play with. This time out, we'll work with a simple substitution — ammonium bromide for potassium bromide. The recipe is identical to my modification of Kodak AJ-12 except the 5 g of KBr is replaced by A Snippet of History In 1871, a British physician, Richard Leach Maddox, made the first satisfactory gelatin dry plate. Within two years, a German scientist, H.W. Vogel, while trying to conquer halation, discovered ortho sensitization. In the same year, the first commercial dry plates came on the market. By 1877, Britannia Works Company (later Ilford) was up and running, followed almost immediately by Eastman Kodak Company in the US. Those are the big names in history. But, in the beginning, there were dozens upon dozens of small companies, each competing for a piece of the revolution. Often, the entire R&D department of a small company was one individual. Most of them had trouble competing in a cut-throat market. Some went out of business, but many others were bought up by the larger companies. George Eastman gained much of his early research by acquisition. C.E. Kenneth Mees, founder of Kodak Research laboratories, and director of research for half a century, came to Kodak from Wratten & Wainright, Ltd, UK, when that company became part of Kodak. It's hard to tease out of history the exact time, place, and person responsible for every innovation. From the beginning, different ingredients were tried and tested. A great deal of the early research was into gelatin, but also into various chemicals and cooking techniques. There were a lot of dead ends of course, but by and large the research was solid, and new materials followed one upon another. Although it's hard to disagree that each new generation of materials didn't in some way improve upon its predecessors, all along the historical timeline there are brilliant recipes. |

|

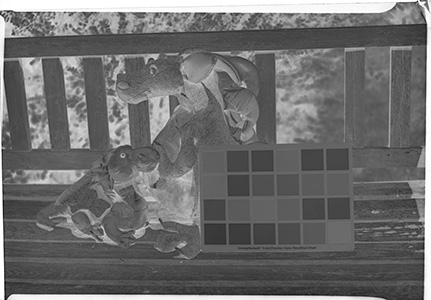

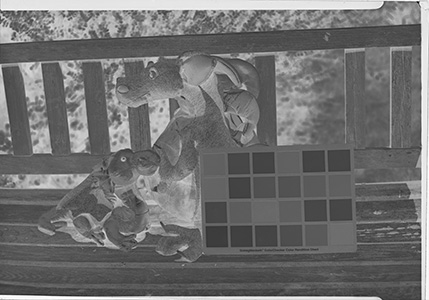

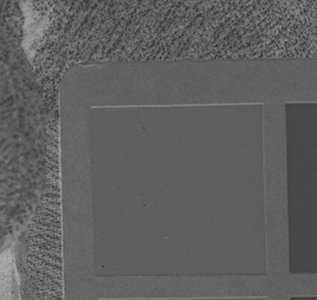

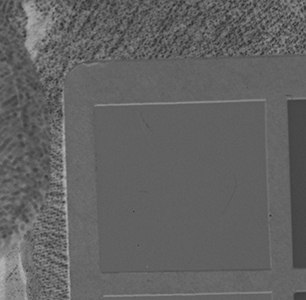

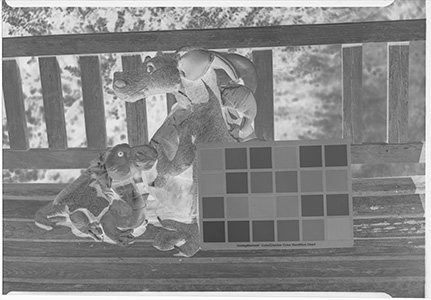

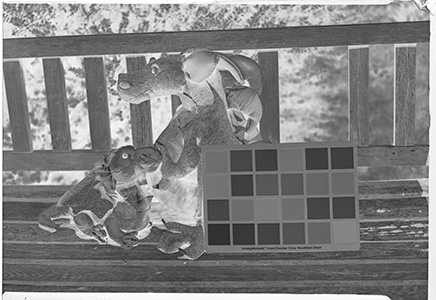

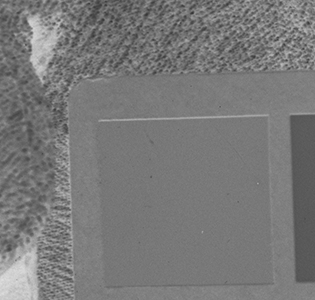

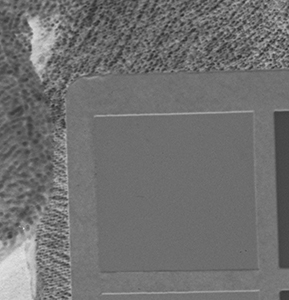

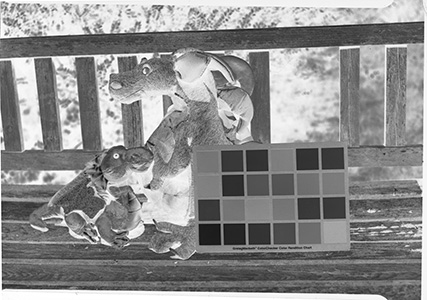

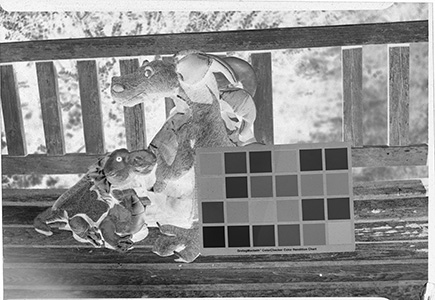

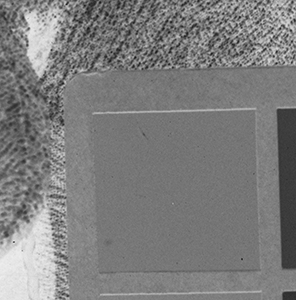

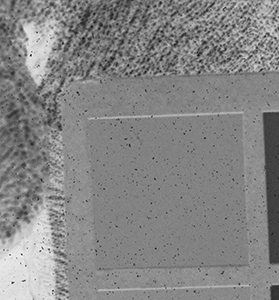

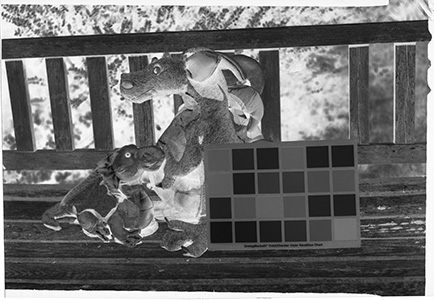

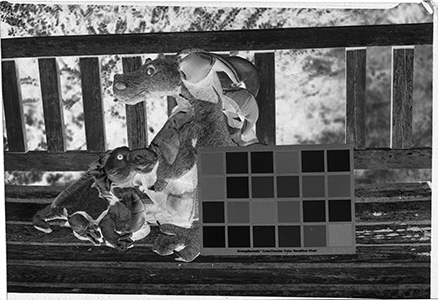

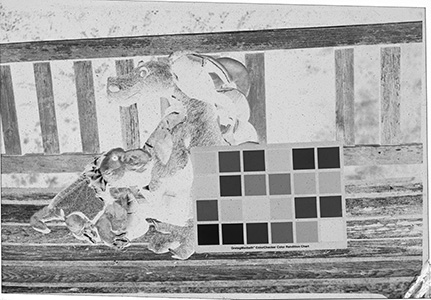

Why the substitution? First, let me hang a flag on the word "improvement." I don't believe one recipe is better than another. Each recipe brings its own characteristics to the game—strengths as well as weaknesses. The definition of "best tools and materials" is totally dependent on the artist. But enough said on that. Hopefully, I'm preaching to the choir. Ammonium bromide, a salt, is on the continuum of incremental improvements to emulsion making. Although a plain silver emulsion cannot normally attain the speed of an emulsion made with silver that has been treated with ammonia, the addition of the ammonium ion to a recipe made with plain silver results in something of a hybrid beast. When NH4Br is dissolved in water, it breaks apart into NH4+ (the ammonium ion) and Br. The bromide combines with silver in the same way as it does when KBr breaks apart, but with a different by-product. Early on, it was recognized that ammonium bromide had advantages over potassium bromide. "A small quantity of ammonia should always be present in either the salts or the first silver solutions, otherwise clots or agglomerates of precipitates may be formed, which will cause black spots on development without exposure..." Understanding why this might be the case requires an elementary understanding of development. The developing part of any developer recipe is the accelerator, an alkali, meaning the pH is over 7. [pH 7 is the neutral point on the acid-base scale of 0 to 14. Acids are below pH 7. The lower the number, the stronger the acid. The higher the number, the stronger the base/alkali.] In developers, the stronger the alkali, the more active/energetic the formulation. High activity is usually associated with an increase in speed, graininess, and/or contrast. Metol is a very weak alkali. That's the reason D23 (metol with sodium sulfite) is a low-activity developer. It produces low contrast, fine grain negatives with good shadow detail. The addition of borax—a little stronger alkali—bumps up the activity a bit. Sodium carbonate, considered a moderate alkali, starts to add serious punch. Serious enough that it can cause peppering in plain silver KBr emulsions. Adonal (Rodinal) at 1:10 concentration is a very high activity developer. I use it with X2Ag emulsion to get ASA 100 in the summer. Ammonium bromide plain silver emulsion, developed in Adonal, 1:10, can achieve handheld speeds in the summer—if the light is strong and you can live with high contrast. But, develop AJ-12 made with KBr in Adonal and you get a disaster of pepper and fog. The following set of illustrations runs through a comparison between KBr and AmBr negatives. Except for the substitution of NH4Br (a.k.a. "AmBr") for KBr, the emulsions were prepared identically, then exposed at the same time and developed together. Ammonium bromide negatives are on the left and potassium bromide negatives are on the right. The negatives are all 2½ x 3½ inches, coated on Dura-lar Wet Media Film. The enlarged crops are the upper left hand square of the chart. The negatives were scanned in a Nikon 9000 at 4000 dpi (no adjustments) and then resized to 150 dpi jpgs. The Nikon 9000 is an excellent scanner, but a scan is still only a virtual representation. In reality, except when badly fogged, all of the KBr negatives are a little more punchy/contrasty than the AmBr negatives. What this means is that for a given exposure, the AmBr negatives have a little more detail in the shadows and the highlights aren't quite as dense. As always, my research is not in any way exhaustive or ultimately conclusive in all circumstances. There's good reason that a small library of books have been written on this subject. |

|

|

Exposure: f/16, 5 sec.

|

|

|

|

Exposure: f/8, 1 sec.

|

|

|

|

Exposure: f/11, ½ sec.

|

|

|

|

Exposure: f/32, 1 sec.

|

|

|

|

Exposure: f/8, 1/60 sec.

|

|

|

Here's a question for another day. This is KBr emulsion. I really wanted just a little more speed to stop the fuchsias from fluttering. I decided to try dumping equal amounts of D23 and sodium carbonate accelerator together and develop for 8 minutes. Peppering. I didn't have any more KBr emulsion to test whether or not splitting the baths would help. It could be that NaCarb is too active for a KBr emulsion. Fortunately, it works very effectively with the ammonium bromide emulsion. |

|

|

Continued... |

|